Nutrient stratification in no-till: How to take soil samples

By Frederik Vilhelm Larsen, Crop Consultant, Agroganic

Are you taking your soil samples correctly? It’s winter, and that means time for field planning but also for soil sampling. A common question we often have to address in no-till and reduced tillage agriculture is: how should we handle liming and soil sampling in non-till cultivation systems?

When is stratification an issue?

The term “stratification” means that there can be a concentration difference in the pH and nutrients in a soil profile depending on the depth. For example, if phosphorus is applied to the soil surface, there is more phosphorus available in the topmost centimeters.

It’s usually not a problem if the soil is regularly mixed by harrowing and, if necessary, plowing. If deeper soil tillage is omitted, then stratification can begin. This can be relevant if superficial harrowing (5-8cm) is primarily performed, or direct seeding is practiced.

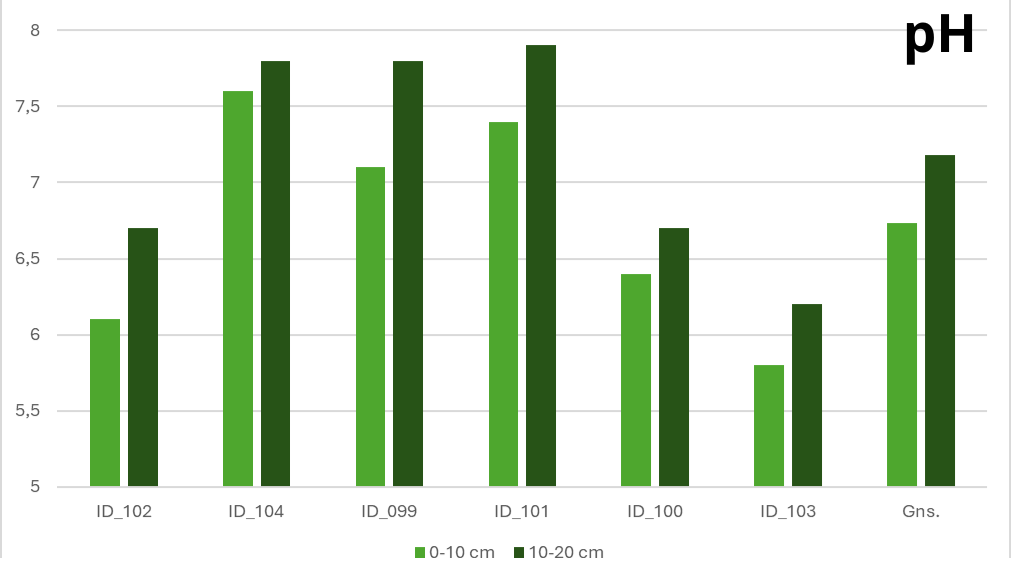

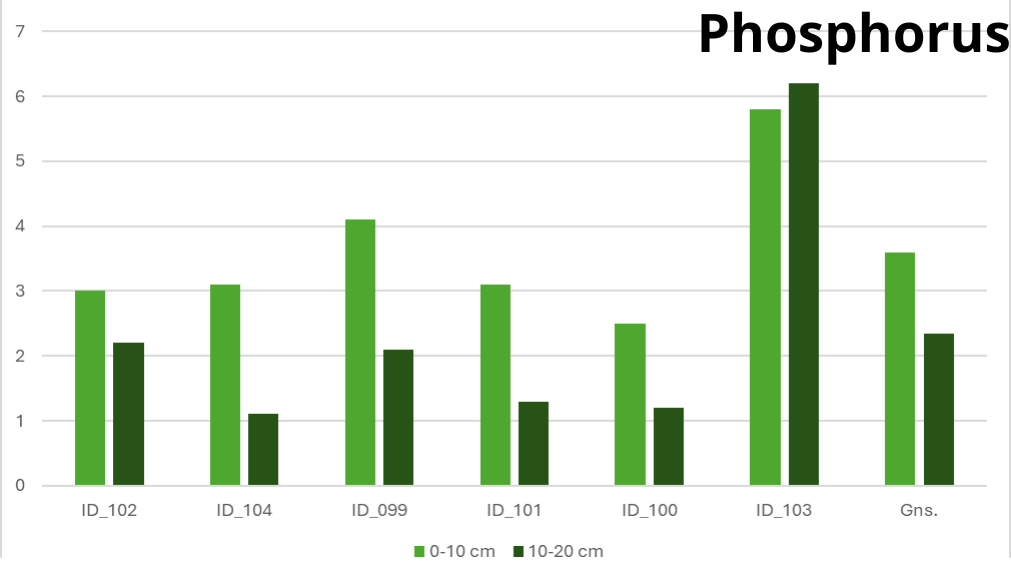

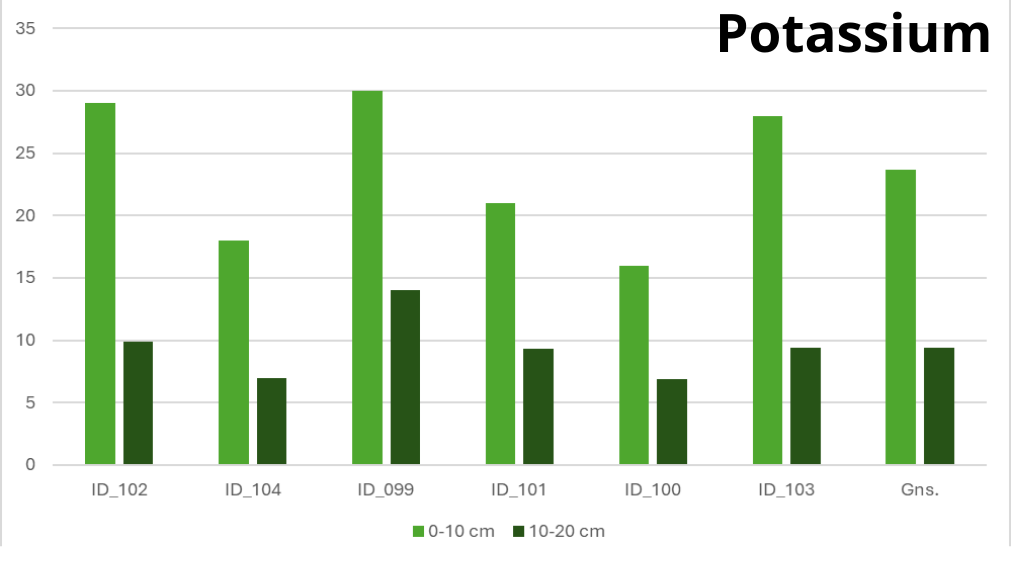

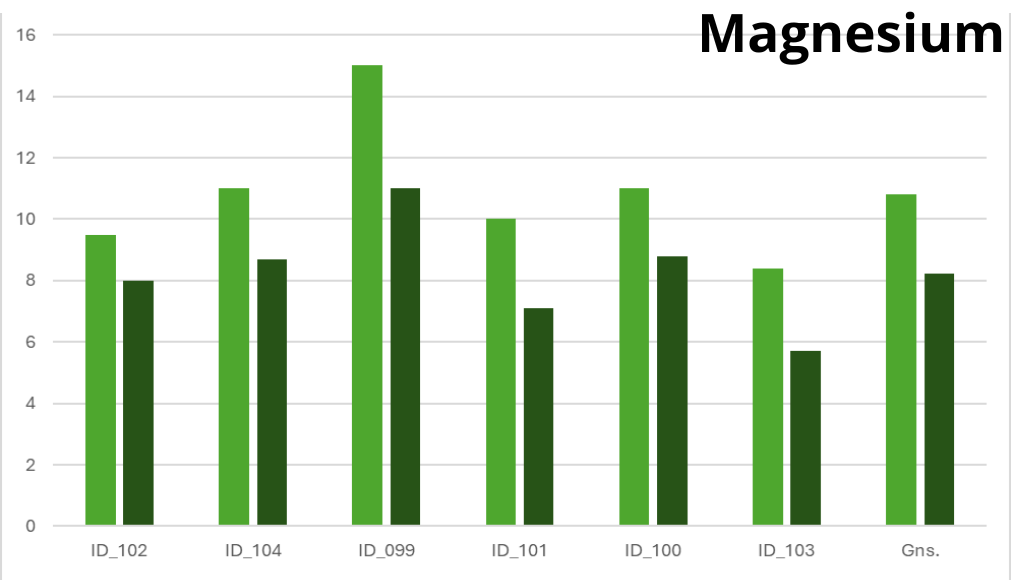

This is something we can observe in practice. Attached figures (bottom of the article) provide some specific examples. For instance, pH is approximately 0.5 lower in the upper 10cm of the soil profile compared to the next 10cm. Similarly, there is a significant difference in phosphorus levels between the upper and lower samples in our experiment. If only regular soil samples (0-25cm) are taken, it might average out an acute issue in the top centimeters of the soil profile.

What can we use this knowledge for?

First and foremost, we must consider that the sampling depth for soil samples should match our soil cultivation history and strategy. If we don’t till the soil for an extended period and sow directly, we should be prepared to deal with local acidification in the top of the soil. Fortunately, this is not necessarily a problem and can be easily solved by applying small amounts of agricultural lime (e.g., 500-1000kg/ha) every few years to avoid falling behind.

How to deal with phosphorus stratification in plowed and no-till systems

Phosphorus stratification can be worse because phosphorus hardly moves in the soil. It becomes particularly problematic in dry years because as soon as the soil dries out, nutrients cannot move in the soil solution.

In this case, a tentative argument for rotational plowing can be made. Thus, after nutrient stratification (probably taking at least 5 years) in the top centimeters of the soil profile, turning the soil upside down and starting the process anew is possible.

If direct seeding and/or superficial harrowing are practiced, some preventive measures need to be considered. Two specific solutions are possible.

First, in a direct seeding system, work towards applying phosphorus by placing it with the seeder. Never apply on the soil surface through broad spreading. This way, P is moved a few centimeters into the soil where it is closer to the crop’s roots. Similarly, applying manure into the soil would be relevant if practically possible.

Secondly, one can consider a strategy for phosphorus application through foliar feeding directly with flat-spray nozzles on the crop. This way, P can be applied directly on crop leaves, avoiding application on the soil.

Concentration differences after many years of direct seeding show that phosphorus is very immobile in the soil. That is, if there is a risk of phosphorus leaching, it is mainly due to particle runoff from the soil surface (wind/water erosion). This is effectively eliminated by practicing direct seeding.